Table of Content:

- 1 Structured cabling, in plain English

- 2 The parts you’ll see in a real structured cabling system

- 3 How to tell if your cabling is truly “structured” (or just neatly bundled)

- 4 Planning tips that save money later (and reduce downtime)

- 5 FAQs

- 5.1 What is a structured cabling system in one sentence?

- 5.2 How is structured cabling different from point-to-point cabling?

- 5.3 What are the main components of structured cabling?

- 5.4 Does structured cabling improve network speed?

- 5.5 How do I know if my cabling is installed correctly?

- 5.6 Is fiber always better than copper for structured cabling?

- 5.7 What documentation should I request after a cabling project?

- 6 Conclusion

When people ask “what is a structured cabling system,” they’re usually not asking for a textbook definition. They’re asking because something hurts: the server room looks like spaghetti, the last office reconfiguration broke half the drops, or a “quick” camera add turned into a ceiling-tile scavenger hunt.

Structured cabling is the opposite of that chaos. It’s the idea that your building’s data, voice, and low-voltage connections should be installed like a piece of infrastructure—not like a pile of one-off fixes.

If you’re a facilities manager, IT lead, or operations person who just needs a plain-English answer (plus what to look for in the real world), this is for you.

Key Takeaways

- Structured cabling is a standards-based way to design and install building cabling so moves/adds/changes are predictable—not a fire drill.

- It’s organized around defined areas (entrance, equipment room, telecom rooms, backbone, horizontal runs, work areas), not random point-to-point wiring.

- The best systems are labeled, documented, and tested—so troubleshooting doesn’t start with guessing.

- “Future-proofing” is less about buying the fanciest cable and more about planning pathways, rack space, and upgrade-friendly design.

- You can evaluate cabling quality with a quick walkthrough: labeling, pathways, bend radius, patching discipline, and test reports tell the story.

Structured cabling, in plain English

A structured cabling system is a planned, standardized way to connect your building’s devices—computers, phones, Wi-Fi access points, printers, cameras, badge readers, conference rooms—back to network equipment using consistent pathways, termination points, and labeling. Instead of running a separate cable every time someone needs something (“just pull one more line to that corner office”), you build a cabling “framework” that makes changes easy to manage.

The big difference is that structured cabling is designed as a system. It uses predictable connection points (like patch panels and telecom rooms) so that when you need to add 12 desks or relocate a department, you’re mostly patching and extending within the framework—not tearing ceilings apart.

If you’re mapping this to a real project, the work usually starts with a structured cabling plan and ends with documentation and testing. That’s why teams planning a new buildout—or cleaning up a messy one—often start by scoping a proper structured cabling installation so the wiring matches how the building actually operates.

There’s a reason so many orgs formalize cabling rules. For example, Caltech’s campus standards reference widely used TIA standards (including TIA-568 for cabling and TIA-606 for administration/labeling) as part of keeping networks consistent across buildings and over time. That kind of standardization is the whole point of structured cabling.

The parts you’ll see in a real structured cabling system

You don’t need to memorize standards language to understand the structure. You just need to recognize the “zones” and what they do.

Think of it like a city’s road system: highways (backbone), streets (horizontal), intersections (patch panels), and addresses (labels). In most commercial environments, the system is organized around six practical building blocks:

- Entrance facility: where carrier services and outside plant come into the building (often fiber, sometimes copper, sometimes both).

- Equipment room: the main home for core networking gear (switches, routers, firewalls, servers, UPS).

- Telecommunications rooms (TRs) / enclosures: intermediate rooms or closets that serve a floor or area—this is where horizontal runs usually terminate.

- Backbone cabling: high-capacity links between the main equipment area and telecom rooms (often fiber, sometimes copper depending on requirements).

- Horizontal cabling: the “last leg” from a TR to work areas—office drops, WAPs, printers, cameras, etc.

- Work area: the endpoint—jacks, faceplates, furniture feeds, device connections.

NIST notes that codes and standards help establish minimum criteria for design and construction, and specifically points to ANSI/TIA standards used for planning and installation of structured cabling across premises types. In other words: the structure isn’t arbitrary; it exists so buildings can support changing tech without reinventing the wheel every time.

A practical example: you’re expanding a customer support team into a new suite. With point-to-point wiring, you might run cables from each desk directly back to wherever the “closest switch” happens to be. With structured cabling, you extend horizontal runs to the nearest TR, terminate cleanly on a patch panel, label everything consistently, then patch into the network. The difference shows up later—when that suite gets rearranged again.

This is also where “network cabling” as a service can be misunderstood. Many teams think it means “pull some Cat6 and we’re done.” A good network cabling installation should include the structured elements: pathways, terminations, labeling discipline, and documentation—so the next change isn’t a mystery project.

How to tell if your cabling is truly “structured” (or just neatly bundled)

A lot of cabling can look tidy on day one. The question is whether it stays manageable after two years of office churn, vendor changes, and “quick adds.”

Here’s what to check on a walkthrough—no special tools required:

1) Labeling that matches reality

Every cable and port should have a label that maps to a patch panel position and a destination (room/desk/device). If labels exist but don’t match what’s actually connected, you’ll lose trust fast—and the system becomes “structured in name only.” Caltech’s published standards list includes TIA/EIA-606 (administration) alongside the cabling standards, which is a subtle hint: labeling isn’t optional if you want a system you can run long-term.

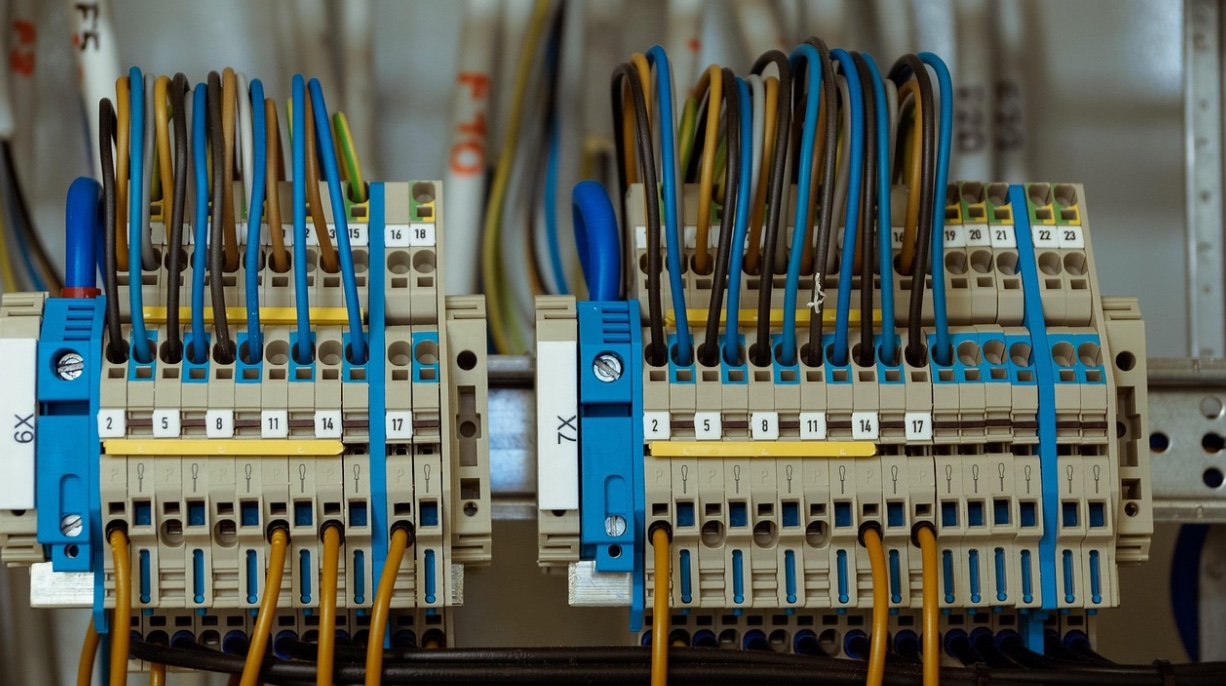

2) Patch panels and patching discipline

Cables should terminate on patch panels (not directly into switches), with patch cords used for changes. If you see permanent horizontal cables jammed straight into switch ports, it’s harder to manage, easier to damage ports, and a pain to reconfigure.

3) Pathways that look intentional

Look above ceiling tiles and in risers. You want proper cable trays, J-hooks, conduit where appropriate, and separation from electrical sources that can create interference. You also want slack management that doesn’t turn into coils the size of tires.

4) Bend radius and strain relief

Even without a spec sheet, you can spot bad practices: tight kinks, crushed bundles, cable ties cinched like zip-tie handcuffs, or fiber runs with questionable bends. These issues don’t always fail immediately—they create intermittent errors that ruin your week later.

5) Documentation and test results

Ask for as-built drawings (even a simple plan), labeling scheme documentation, and certification/test reports for copper and fiber. If the answer is “we didn’t do that,” you’re inheriting risk. You’ll pay for it later in troubleshooting hours and repeat work.

A good rule: if you can’t confidently answer “what does this port connect to?” without unplugging things, the system is not functioning as structured cabling—no matter how clean the rack looks.

Planning tips that save money later (and reduce downtime)

Structured cabling doesn’t mean overspending. It means making choices that reduce rework and make change predictable. These are the decisions that tend to matter most.

Design for the building’s life, not this quarter’s layout

Your office layout will change faster than your walls. Cisco notes that typical data center life cycles can run 10–15 years and that cabling architecture choices have a major impact on the ability to adapt to changes and moves/adds/changes (MACs). Even outside a data center, the same logic holds: cabling that’s hard to modify becomes a tax on every future project.

Build in capacity where it’s cheap to do so

Adding a few extra pathways (tray space, sleeves, conduit capacity) during a remodel is usually far cheaper than trying to add them once the ceiling is sealed and the tenant is live. Capacity isn’t only “extra cable drops.” It’s physical space to route, separate, and protect the cabling you’ll inevitably add.

Be clear about copper vs. fiber—and where each belongs

Copper (Cat6/Cat6A in many offices) is great for endpoint runs and Power over Ethernet devices. Fiber is often the better choice for backbone links, longer distances, and bandwidth-heavy interconnects. If your growth plan includes more cameras, more access points, or more high-speed uplinks between IDFs/MDF, it’s worth planning fiber where it counts. Teams doing high-speed uplinks or campus-style builds often include fiber optic cabling as part of the structured design, not as an afterthought when copper hits limits.

Make MACs a normal process, not an emergency

Moves/adds/changes will happen. The goal is that your process is: update the record, patch at the panel, test, move on. If every MAC requires guessing which cable is which, you’ve built a fragile environment that depends on tribal knowledge.

Ask better questions before you approve the work

If you’re scoping a job (new buildout, refresh, cleanup), these questions tend to separate “cables installed” from “system delivered”:

- What labeling standard will be used, and what will the labels correspond to (room/port/panel)?

- Will patch panels be used for all horizontal terminations?

- What testing/certification will be provided, and in what format?

- How will pathways be routed and supported (tray/J-hooks/conduit), and how will separation from electrical be handled?

- What documentation is included (as-builts, port maps, rack elevation, photos)?

You’re not being picky. You’re preventing the slow, expensive drift back into chaos.

FAQs

What is a structured cabling system in one sentence?

It’s a standards-based way to install building cabling with defined pathways, termination points, labeling, and documentation so changes and troubleshooting are predictable.

How is structured cabling different from point-to-point cabling?

Point-to-point cabling runs a direct cable for each device need; structured cabling uses telecom rooms, patch panels, and organized subsystems so you can reconfigure without re-running everything.

What are the main components of structured cabling?

Most commercial setups include an entrance facility, equipment room, telecom rooms, backbone cabling, horizontal cabling, and work areas—plus patch panels and cable management to keep it serviceable.

Does structured cabling improve network speed?

It won’t make a slow internet connection magically fast, but good design and installation reduce errors, interference, and downtime—helping your network perform consistently at its rated speeds.

How do I know if my cabling is installed correctly?

Look for consistent labeling, patch panels (not direct switch terminations), supported pathways, clean bend radius/strain relief, and test reports that match the installed links.

Is fiber always better than copper for structured cabling?

Not always. Copper is often ideal for endpoint runs and PoE devices; fiber is typically best for backbone links, long distances, and high-bandwidth interconnects between rooms or floors.

What documentation should I request after a cabling project?

At minimum: port maps/labeling scheme, as-built drawings (even simplified), rack/patch panel layouts, and certification/test results for installed copper and fiber links.

Conclusion

A structured cabling system is basically the difference between a building that’s easy to run and a building that slowly turns every change into a mini-crisis: build the wiring like infrastructure, with standards, labels, and a plan, and the day-to-day work gets calmer fast.