If you’ve ever opened a telecom room door and immediately regretted it, you already know why fiber decisions matter. One wrong assumption—“We’ll just run whatever cable we used last time”—and you’re stuck with links that won’t certify, patch panels that don’t match the optics you bought, and a ceiling full of rework.

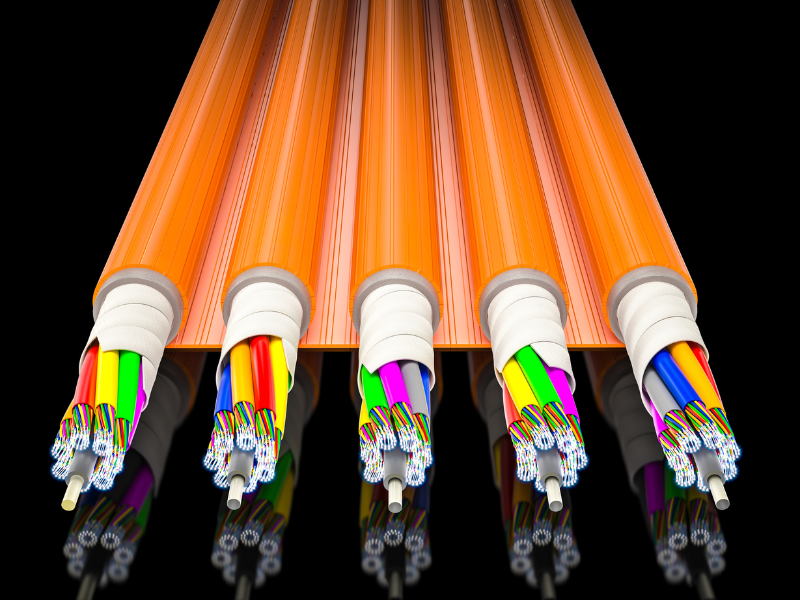

The good news is that “types of fiber optic cables” doesn’t have to be a confusing rabbit hole. Most commercial projects boil down to a handful of practical choices: single-mode vs. multimode, the OM/OS grades, the right construction for the environment, and a few install habits that keep everything readable six months later.

This is a plain-English guide for facilities and IT teams who want fiber that performs well, stays organized, and doesn’t turn every add/change into a disruption.

Key Takeaways

- Start with the link’s distance and speed, then pick single-mode (OS) or multimode (OM)—not the other way around.

- OM3/OM4 are common inside buildings and data closets; OS2 is a workhorse for longer runs and backbone links.

- Cable construction matters as much as the glass: indoor/outdoor, tight-buffer vs. loose-tube, and armored choices prevent damage and code issues.

- “Clean install” usually comes down to basics: pathways, bend radius, pull tension, labeling, and test reports you can actually use.

- Don’t let connectors, polarity, or cleanliness be an afterthought—they’re the quiet source of most fiber headaches.

1) The core “types”: single-mode vs. multimode, and what OM/OS actually means

At the highest level, fiber falls into two buckets: single-mode and multimode. Single-mode uses a very small core and is designed for longer distances; multimode uses a larger core and is commonly used for shorter links inside buildings and campuses. The tradeoff is rarely “which is better” and more “which matches the link budget, optics, and future plans.” Cisco’s primer is a good reference for the practical differences and why implementation costs often depend on the optics/transceivers, not just the cable.

The naming you’ll see on quotes and reels—OM1/OM2/OM3/OM4/OM5 and OS1/OS2—is the industry shorthand for fiber categories. Think of it like a label that tells you what performance class you’re dealing with and, by extension, what kinds of Ethernet speeds and distances are realistic. Fluke Networks summarizes how the OM (multimode) and OS (single-mode) designations align with standards and why the labels exist in the first place.

Here’s the quick, usable mapping most teams care about:

| Fiber type | Mode | Typical use case | Common “why” |

| OM1 / OM2 | Multimode | Older buildings, legacy gear | Often existing installs; limited for modern high-speed distances |

| OM3 / OM4 | Multimode | Inside-building links, data closets, server rooms | Solid for high bandwidth over shorter distances; widely available |

| OM5 | Multimode | Specialized short-range, multi-wavelength scenarios | Less common; only pick when you have a clear design reason |

| OS1 | Single-mode | Indoor, tighter-buffered single-mode | Can make sense in controlled indoor environments |

| OS2 | Single-mode | Backbone, building-to-building, longer runs | Flexible choice for distance and upgrades |

A practical planning tip: if you’re doing anything that smells like a backbone—MDF to IDF, floor-to-floor, building-to-building—single-mode (often OS2) tends to keep options open. If you’re linking racks inside a data closet or a single floor where distances are known and short, OM3/OM4 is frequently the straightforward pick. And if the project is still fuzzy—“we’re renovating now, but we might add an adjacent suite later”—make that uncertainty explicit in the design assumptions before you buy a single reel.

If you’re scoping a project and need a sanity check on what fits your layout, it helps to think in terms of the whole job: pathway, termination, testing, and documentation—not just the cable jacket. That’s why many teams start with a defined scope like fiber optic cabling rather than buying materials first and trying to force-fit decisions onsite.

2) Cable construction choices that prevent damage, failed inspections, and re-pulls

Once you’ve picked the mode and grade, the next “type” decision is the construction—what protects the fiber, how it behaves during pulls, and where it’s allowed to live. This is where a lot of installs go sideways, because the fiber itself might be correct, but the cable is wrong for the environment.

Start with the two broad constructions you’ll hear about:

- Tight-buffered fiber: more common indoors, easier to handle at terminations, often used in risers and telecom rooms.

- Loose-tube fiber: common in outdoor or harsher environments because it protects fibers from moisture and temperature changes.

Then layer in environmental ratings. The big ones in commercial buildings are plenum and riser. Plenum-rated cable is designed for air-handling spaces (like many ceiling plenums) and can be required by code in those areas. Riser-rated cable is intended for vertical shafts and floor-to-floor runs. The point isn’t to memorize the abbreviations—it’s to match the cable to where it will physically run. If you guess and you’re wrong, the fix is rarely small.

Also consider whether you need armored fiber. Armored cable can be a good fit in areas where you don’t fully control the pathway (warehouse ceilings, exposed runs, shared corridors) or where rodents and physical damage are real concerns. The tradeoff is stiffness, bend handling, and sometimes termination complexity—so it’s not a default choice, but it’s a useful tool when the environment demands it.

Two examples that come up a lot:

- Renovation with open ceilings: If trades are active and pathways are exposed, cable protection and routing discipline matter more than usual. A slightly more rugged construction can save you from “mystery” intermittent issues later.

- Retail buildouts with fast timelines: If you’re adding IDFs and cameras and the design keeps changing, choosing a cable type that terminates cleanly (and labeling consistently) is what keeps you from chasing your tail at turnover.

If you want the result to behave like building infrastructure—not a patchwork—make sure the cabling plan matches the full system: rooms, pathways, and administration. That’s the same mindset behind a good structured cabling installation, even when the focus is fiber.

3) The “parts” that make or break clean installs: connectors, polarity, labeling, and testing

Fiber problems are often blamed on the cable type, but the root cause is usually in the parts and finishing details: connectors, polarity, cleanliness, and records.

Connector types: pick for the gear you’re using, not what’s easiest to find

For many enterprise networks, LC connectors are common at the equipment side, while SC shows up in a lot of building infrastructure and older panels. In higher-density environments (data centers, aggregation links), MPO/MTP can make sense because it packs multiple fibers into one connector—great when designed correctly, painful when it isn’t.

The planning move is simple: list your endpoints (switches, optics modules, panels) and confirm what they require before you lock in the termination hardware. You want to avoid ordering a stack of patch cords that don’t match the transceivers you already own.

Polarity: the quiet detail that causes “it should work” outages

With duplex links it’s usually manageable, but with MPO-style trunks it’s easy to end up with a polarity mismatch—everything looks connected, but transmit/receive aren’t aligned. That’s not a “bad fiber” situation; it’s a system design and documentation situation. If you’re upgrading an existing plant, document what’s there (including how patch panels are pinned) before mixing new trunks with old cassettes.

Color codes and identification: don’t rely on memory

Color matters more than people admit because it’s how humans do fast visual checks. Jacket colors, connector colors, and labeling conventions help your team avoid plugging the wrong thing during a change window. The Fiber Optic Association has a straightforward reference on common fiber color codes and what they typically indicate.

A practical standard you can adopt even in smaller environments: every fiber link should have a consistent ID that ties together (1) the patch panel port, (2) the destination, and (3) the test record. If any of those three are missing, the “system” is incomplete and troubleshooting gets expensive.

Testing and acceptance: what to ask for so results are usable

For new fiber, “it lights up” isn’t the finish line. Ask for test documentation that matches the scope:

- Loss testing (so you know the link meets budget)

- Certification records tied to the labeling scheme

- OTDR traces where appropriate (especially on longer runs or when splicing is involved)

If you’re coordinating multiple trades, it also helps to have one team accountable for end-to-end testing and documentation so the handoffs don’t become guesswork.

Finally, clean installs don’t happen by accident. The basics that consistently keep fiber tidy are boring, but they work: planned pathways, controlled slack, protected terminations, and patching that’s done with intent. If you’re dealing with a mixed environment (copper, fiber, cameras, access points), coordinating the full pathway and labeling approach under one scope—like network cabling installation—is often what prevents the “two racks, five labeling systems” scenario.

Conclusion

Choosing among the types of fiber optic cables gets a lot easier when you treat it like a building decision: match the fiber mode and grade to the link needs, match the construction to the environment, and finish the job with connectors, polarity, labeling, and testing that make the system easy to live with.

FAQs

What are the main types of fiber optic cables?

The two main types are single-mode and multimode. Single-mode is typically used for longer distances and backbone links, while multimode is common for shorter links inside buildings and data closets.

What’s the difference between OM and OS fiber?

OM categories (OM1–OM5) are multimode performance classes, and OS categories (OS1–OS2) are single-mode classes. The label helps indicate expected performance characteristics and typical deployment scenarios.

Should I choose OM3 or OM4 for an office or data closet?

OM3 is widely used for many short-range high-bandwidth links, while OM4 generally supports longer distances at similar speeds in comparable conditions. If you’re near distance limits or want extra margin, OM4 can be a safer bet—assuming optics and budget align.

When does OS2 make more sense than multimode?

OS2 is often chosen for longer runs, building-to-building, and backbone cabling where upgrade flexibility matters. It can also reduce future constraints when you’re unsure how needs will grow over time.

What’s the difference between tight-buffered and loose-tube fiber?

Tight-buffered fiber is common indoors and is generally easier to handle at terminations. Loose-tube fiber is often used outdoors or in harsher environments because it protects fibers from moisture and temperature variation.

What should I request after a fiber installation is complete?

Ask for a port map that matches labels, plus test documentation (loss testing and certification results) tied to each link ID. If splicing or long runs are involved, OTDR traces can help validate workmanship and simplify future troubleshooting.